Why smallholder farmers are key to scaling regenerative agriculture: 10 case studies

- Regenerative Agriculture

- Food Waste Reduction

- Smallholder Farming

- Agritecture

- Regenerative Croplands

- Cropland Restoration

- Polyculture

In order to better understand the potential impact of Regenerative Agriculture (RA) across the developing world and what has been happening among the more than 15 million smallholder farmers using its practices, let’s look at the impact it has had on a single, average farmer among them. Laureano, pictured above, is showing us the nature and results of his switch to RA, which provides him with an impressive list of benefits. One of the many beauties of RA is that it also benefits the rest of the world in multitudinous ways, as there is no contradiction between the individual welfare of the producer and the general welfare of all.

What are these benefits for Laureano, and what is he doing to achieve them? First and foremost, he wants to have enough food to feed his family. This is the highest priority goal of virtually all smallholder farmers in any developing country, whether he is a Mayan from Guatemala, a Quechua from Bolivia, a Luo from Kenya, or a Tai person from Vietnam. In his left hand, Laureano is showing us one medium-sized ear of maize, similar to those he used to harvest four or five years ago from each of his maize plants.

In his right hand, he has two large ears of maize—his average harvest from each plant—which is close to three times his previous harvest. That, in turn, means that his son and his grandchildren will not go hungry. They will be able to go to high school and buy the simple medicines they need and maybe, someday, buy a used pick-up to take their excess produce to market for a better price.

Image credit: Courtesy of Roland Bunch

Laureano will never again have to work as a day laborer on a nearby sugarcane plantation. With the tripling of yields, he now easily produces far more food on his farm than his family needs. And now that his soil is fertile enough to grow most anything else, he is experimenting with several cash crops. That is, he will start feeding other Hondurans. In the process, he is adding biodiversity to his farm, which will enrich the environment, reduce the concentration of pests, and make his farm even more profitable.

A second goal for Laureano, and for other farmers like him, is that he wants to do all this while maintaining his human dignity. He doesn’t want handouts. He doesn’t want to stand in line waiting for a bowl of soup while his children stand behind him, aware that he’s incapable of feeding his own family. At the end of the day, he wants the satisfaction of knowing that what he has achieved in life, he has accomplished himself without dependency or having to beg. One of the beauties of RA is that there is no need for hand-outs because there is nothing needed beyond a handful of seeds for an initial experiment. Giving someone a handful of seeds in a village is not charity; it’s considered a normal, everyday act of friendship.

A third goal for Laureano is to contribute toward the reduction of climate change. You’d be surprised by how many of the world’s villager farmers know about climate change. From television? Maybe. But there are hundreds of millions of Laureanos around the world who know about climate change because they’re living on the receiving end of it.

To give just one example: Fifty years ago, the Laureanos of the world planted according to the calendar. Mayan farmers in Patzum, Guatemala, planted their maize on the 24th of June. If the rainy season hadn’t started a few days before that, it would begin within a week or so. But today, in Patzum, it might start raining as early as the middle of May or as late as early August. I don’t know of a single group of smallholder farmers anywhere in the world without irrigation who can now plant by the calendar.

Planting maize has become like playing the lottery. Sure, you just might win. But it’s far more likely that you will plant your crop when it should start raining, and it won’t rain for a month, so you’ve lost all your seed. Or you’ll wait for the rain, plant your maize when it starts, and then it stops again. Or, wait until you’re sure it’s going to keep raining and wind up planting so late that the rainy season ends before your maize has produced any grain. For many Laureanos in this world, some years it will rain so infrequently that no matter when you plant your maize, you won’t get a decent harvest. So they know something has changed, and none of the farmers I know has any doubt that climate change is one of the causes.

The soft, black earth at Laureano’s feet is a result of the tremendous amounts of carbon-rich organic matter he has put back into the soil. The same organic matter that has tripled his yields is sequestering carbon. He is putting carbon that makes up atmospheric CO2 back in the ground where much of it belongs—where nature had stored it for millennia.

Where did he get all that organic matter? He grew it right there where he would need it. See that weed growing up the maize behind him? That’s what we call a green manure/cover crop (gm/cc). It fixes more nitrogen than his crops will ever need and produces about 60 tons per hectare annually (green weight) of organic matter that makes his soil fertile. He doesn’t have to buy, compost, haul, spread, bury it, or even cut it down. He just plants it. When it dies and he cuts down his maize stalks, it starts fertilizing his soil. Green manure also keeps his soil well-covered so the sun doesn’t heat it up too much. Tropical soils and crops don’t do well with all that heat.

Last but far from least, Laureano doesn’t want all this just for himself. He wants it for his children and his grandchildren. He wants his farm to be sustainable, and it will be. After all, tropical forests represent the height of sustainability, as they have been producing huge amounts of organic matter for tens of millions of years. As Laureano continues to improve his soil, increase his farm’s biodiversity, produce all that organic matter, and keep his soil covered (foresters call it a “litter layer,” agronomists call it a “mulch”), and as he adopts more of the practices described in these case studies, such as growing dispersed shade trees on his farm, his fields will look more and more like tropical forests. They will also function more like tropical forests.

If Laureano’s farm is going to retain its productivity a couple of generations from now, the rich black soil at his feet will have to stay there. He can’t let it go running down the hillside every time it rains. See that grass growing right behind Laureano? It’s part of a contour grass barrier that stops his topsoil from washing down the slope. In fact, Laureano’s son, Marcos, is sitting on the edge of a 60-cm high terrace made up entirely of the soil that the grass has already prevented from washing down the hillside.

Will Laureano actually achieve sustainability? Some gm/cc systems we use have been producing well for over 500 years. Marcos obviously believes in the sustainability of his father’s farm. Rather than having left for Tegucigalpa to search for one of the almost non-existent jobs in the capital’s slums. Marcos is still living in the village, thereby showing that he believes his father’s farm will provide him and his future family with a decent living for at least another generation.

I started by saying that RA would benefit all of humankind. We will all benefit from the end of poverty and hunger in this world. There will be fewer poverty-related diseases that tend to travel by plane to everywhere else. (Interestingly, I wrote this last sentence in 2017, more than two years before the term COVID-19 had even been invented.) There will be more moderate numbers of immigrants clamoring to reach Europe and the US, and fewer needs to provide for the victims of famines. Those of us in the developed world will also have the satisfaction of knowing that we live in a world with a little more economic justice. And when fewer of the sons of the world’s Laureanos are crowding into those deathly slums without opportunities, there will be less civil unrest.

Lastly, it turns out that the farmers and ranchers of the world could sequester a good share of the carbon we need to take out of the atmosphere to keep our world safe. Even fairly simple gm/cc systems can sequester about 6 t/ha/year of long-term carbon in decent tropical soil. As sequestering carbon is a free by-product of producing three times what Laureano did before, his process of developing a sustainable lifestyle will help the rest of us enjoy a more sustainable lifestyle without having to face a global environmental catastrophe.

Of course, RA is not going to storm the world overnight, nor will getting us there be totally free of cost. Some people are going to have to spend the next 25 years training a lot of Laureanos if we’re to get there.

The process will cost each farmer only a few handfuls of seed to get started. No one has ever given Laureano any hand-outs, although he is from a small village in Honduras, a country with a rate of rural malnutrition equal to that of most of sub-Saharan Africa. Furthermore, he is farming on what most farmers from the world’s North would consider a postage stamp of a farm. Yet, in his case and in every case study featured, farmers who have learned to use RA are spreading it to other farmers spontaneously—at no cost to anyone else.

The most positive news of these stories is that we trainers won’t be starting from scratch. There are already well over 15 million other Laureanos out there benefitting from using Regenerative Agriculture. The ten stories selected here are representative of about 7 million of them. I have chosen others to give an idea of the wide variety of RA technologies that exist, and still others, because they illustrate important points about RA or agricultural development in general.

Dogon village in Mali, West Africa. Photo: ID 36654168© Kent0344 | Dreamstime.com

Case study 1: The Dogon “intermittent shade,” Koro, Mali

An ancient technology introduced by the Dogon is “intermittent shade.” Crops across the world’s lowland tropics are increasing production by as much as 40% when grown under well-managed shade trees.

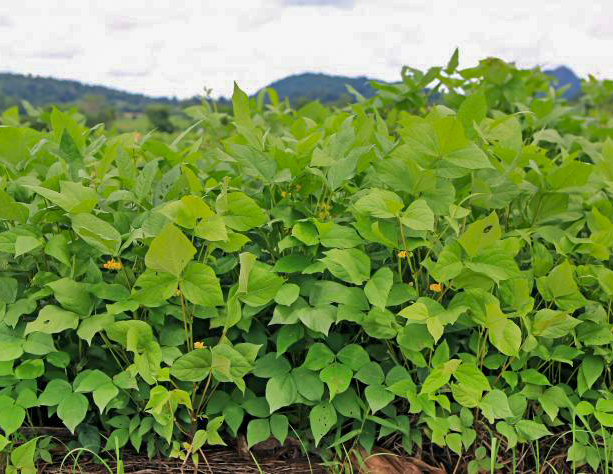

Cowpeas in a field. Photo | Shutterstock

Case study 2: The Lojy Be cowpea, Befandriana Sud, Madagascar

The gift of a unique traditional, drought-resistant, and nutritious cowpea variety increases soil fertility and neighboring crop productivity.

Image credit: Courtesy of Roland Bunch

Case study 3: Conservation Agriculture, EPAGRI, Santa Catarina State, Brazil

Brazil has been a leader in developing what is known as Conservation Agriculture: zero or minimum tillage, crop diversification, and the adoption of green manure and cover crops.

Image credit: Courtesy of Roland Bunch

Case study 4: Integrated development program, World Neighbors/Oxfam, San Martín Jilotepeque, Guatemala

A successful integrated development program demonstrates the diverse nutritional, economic, and social benefits of adopting the techniques of Regenerative Agriculture.

Mucuna pruriens, also called velvet beans. Photo 122551863 © Pitaksunti Montol | Dreamstime.com

Case study 5: The world’s cheapest maize, Honduras, Guatemala, and Mexico

The companion planting of maize with mucuna (velvet beans) is an illustration of the success of utilizing all Regenerative Agriculture principles.

Image credit: Courtesy of Roland Bunch

Case study 6: Micro-terraces, World Neighbors, Guacamayas, Honduras

The Cantarranas Program taught people how to make simple, irrigated micro-terraces to enable regenerative vegetable farming on very steep terrain.

.jpg)

Tephrosia purpurea. Photo 254701398 © Privin Sathy | Dreamstime.com

Case study 7: Tephrosia fallow, Bamenda, Cameroon

The accidental discovery by a small farmer of the soil-enriching properties of a plant called tephrosia has enabled thousands of regional farmers to reduce fallow time and plant crops more frequently.

_resized.jpg)

Case study 8: Famine prevention, twelve African nations

Addressing severe famine, the author works with nations that are suffering extreme drought and soil infertility, showing dramatic results with green manure and ground cover techniques to improve soil conditions.

Caste study 9: Dispersed shade with gliricidia, Imagine Afrika/Better Soils, Better Lives, southern Malawi

The gliricidia tree is being planted by farmers as a “dispersed shade,” which creates light shade that covers the entire field evenly. Together with other regenerative practices, it has shown stunning success in improving soil conditions and productivity.

Case study 10: Farmer-managed Natural Regeneration of Trees (FMNR), ten African nations

In most of the drought-prone areas of the tropical world, there are “underground forests” of live tree roots beneath farmers’ fields that could restore forest cover. This discovery led to the FMNR revolution, which has restored millions of hectares and brought agricultural success to some of the world’s most hostile environments.

Learn more about Regenerative Agriculture