Meet the magnificent North American elk: Bioindicators of a healthy ecosystem

- Nature Conservation

- Land Conservation

- Iconic Species

- Wildlife

- Mammals

- Northern America Realm

- American West

One Earth’s “Species of the Week” series highlights an iconic species that represents the unique biogeography of each of the 185 bioregions of the Earth.

The elk in North America (Cervus canadensis) is the largest of the three red deer that dwell in the Northern Hemisphere of the planet. Originally evolved for life in Central Asia, prominently Tibet and West China, the red deer spread eastward into North America over the Bering Strait after the ice age 12,000 years ago.

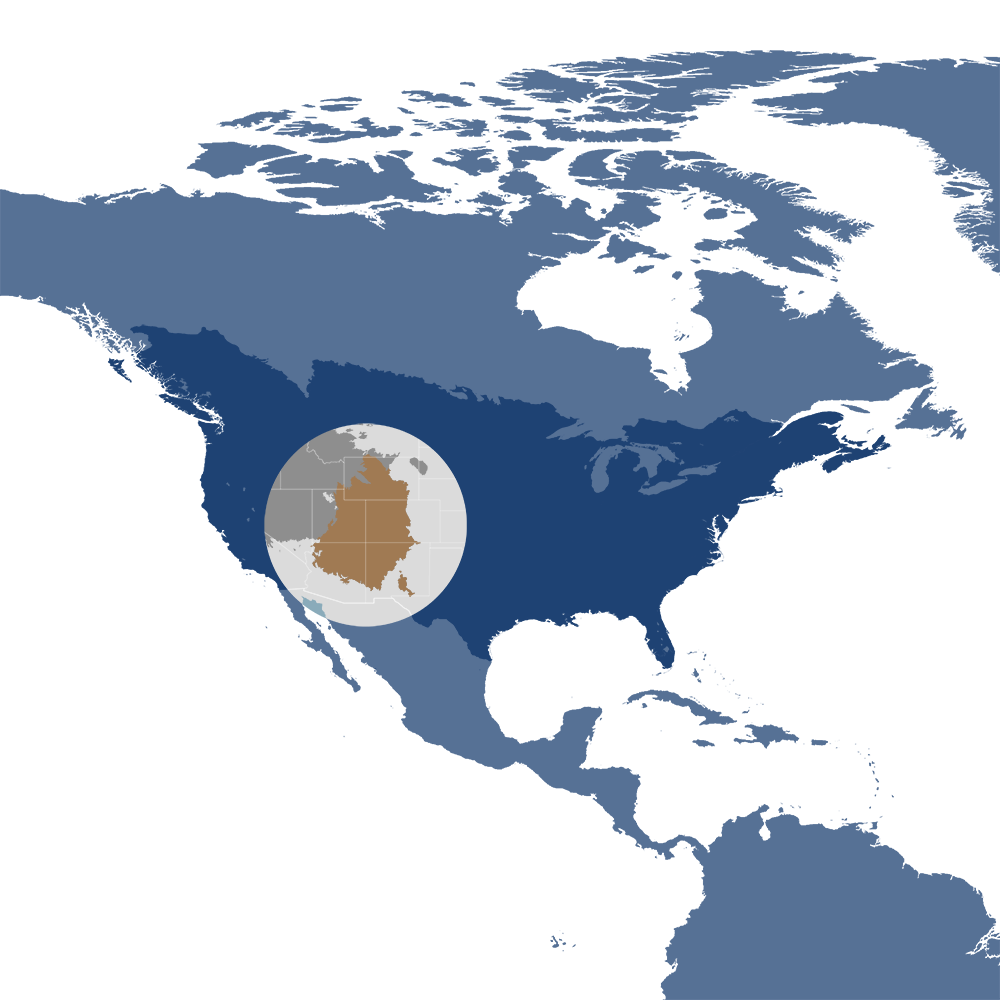

The elk (Cervus canadensis) is the iconic species of the Colorado Plateau & Mountain Forests bioregion (NA19) located in the American West subrealm of Northern America.

Etymology and names across cultures

The European red deer was named ‘elk’ by the Germanic people, which means ‘stag’ or ‘hart’ in reference to the male adult. In North America, it is called the wapiti by the Cree from the Northern Prairie and Aspen Forests and also by the Shawnee from the Southern Prairie Mixed Grasslands. The Lakota from the Northern Prairies call it heháka.

Population patterns and movements

In North America, the elk population once was as high as 10 million, but in the 1800s, it became almost extinct next to their bison and Native American human relatives due to the settler takeover. Today, about one million elk occupy the Yukon, British Columbia, and Alberta in Canada, as well as California, Iowa, Wyoming, Yellowstone National Park, the Rocky Mountains in the US, and forested areas and meadows of Northern Mexico.

Elk are always moving to fields with abundant new green shoots and herbs that, depending on the time of the year, can be found in dense forests, aspen parklands, alpine meadows, sagebrush flats, open grasslands, and swampy valleys. Winter-summer herd migrations can extend for several hundred kilometers, and each herd has a particular ranging area.

A closeup of bull elks on a cold morning in Grand Teton National Park, Wyoming. Image credit: Wirestock | Envato Elements

Migration insights from extensive research

Biologist, elk specialist, and National Geographic Explorer Arthur Middleton analyzed geolocation data for herds in the area covered by Yellowstone National Park, Grand Teton National Park, and the Wind River Indian Reservation. From 2000 to 2015, Middleton monitored the elk population and produced a map called Elk Migrations of the Greater Yellowstone Ecosystem, which can be found in the National Geographic Magazine.

Physical traits and life cycle

Both males and females can reach 1.5 meters (5 ft) tall at the shoulder and 2.4 meters (8 ft) from head to tail. Alberta provides habitat for the largest of elk, which can reach up to 500 kilograms (1,100 lb). California elk reach about 110 kilograms (223 lb), and the size and weight of females tend to be similar to that of males.

Both bull (stag) elk and cow (hind) elk have a reddish brown coat with a light tan on top and a white patch under the tail. In winter, the coat stays the same, but the neck mane grows darker. Towards the end of winter, the coat becomes shaggy, and as spring begins, the coat is replaced by a new one.

Bull elk lip curling. Image credit: Matt Cuda | Envato Elements

All about those antlers

The stag carries a massive 10 to 12 kilograms (22-26 lb) set of antlers, each branching into anywhere from six to 10 tines (points). The antlers are made of living tissue covered with a thick velvet that provides protection and also supplies calcium and minerals to the antlers through small blood vessels.

Antlers begin to grow at the age of two, and they become bigger every new cycle of regrowth, which is once a year. The antlers are retained for about 185 days in the American elk versus 150 for the European red deer.

Behavioral patterns and reproduction

Elk herds exhibit complex social structures, often led by matriarchal females, with herd sizes varying seasonally and regionally. During the breeding season in autumn, the stag elk becomes particularly protective of its harem of one to 12 females.

During the rut, their communication with intruders includes stomping their hooves and sticking their tongues in aggressive manners; in calmer times of the rut season, the landscape is filled with high-pitched bugling calls.

Gestation lasts 255 days for the American elk and 235 for the European deer. Newborn calves weigh 10 kilograms (22 lbs) and are able to stand within twenty minutes, connecting to their mother for milk.

They have spotted skin that provides camouflage from predators during the first two months, fading away soon after. At the age of six months, they have become mature and are as big as a white-tail deer, and in the following spring, they are ready to wander off on their own to find a herd.

The lifespan of a healthy elk is ten to twelve years.

.jpg)

Elk calf. Image credit: Galyna Andrushko | Envato Elements

Diet and ecological role as grazers

Elk have a diverse diet. They consume grasses, sedges, and other herbaceous plants in spring and summer, preferring these over browse. In winter, they feed on lichens, conifer needles, softwood bark, and green shoots as they come up after the snowmelt.

Their feeding habits are influenced by factors such as winter severity, habitat type, human disturbance, and predator presence, but most importantly, by the quality of grasses.

As keystone species, their grazing habits determine the quality of the grassland and topsoil, which in turn affects plant diversity, nutrient cycling, and the distribution of other species.

Essential to predators and habitat bioindicators

Elk populations are crucial in supporting predator populations and regulating prey dynamics, contributing to overall ecosystem health. Healthy elk are critical for the diet of cougars, grizzly bears, wolves, and mountain lions, while the carcass is food for small mammals and vultures.

Herds appear to select habitats that allow them to avoid wolves during summer, but in winter, they seem to rely on other behavioral anti-predator strategies, such as grouping. The herd will not necessarily run away when a cougar or a wolf attacks one member, as by nature, only one weaker member will be preyed upon.

Overall, elk serve as bioindicators, as they reflect the overall health of their habitat through their population number, herd dynamics, their response to stress, and their habitat preferences. In Yellowstone, there are currently seven herds.

Female elk standing in a forest. Image credit: Julie Alex K. | Envato Elements

The elk, a sacred relative

For Native American Nations, the elk is a four-legged relative. In particular, the Lakota are acknowledged as the Elk Nation. The heháka, their highly revered and sacred relative, bestowed upon them the responsibility to take care of life.

The most prominent member of the Elk Nation was Nicholas Black Elk. An Oglala Lakota medicine man who, at a very young age, while on the peak of the highest mountains in South Dakota that now carries his name, saw how “all shapes must live together as one being, in one single hoop.”

From then on, Black Elk dedicated his life to teaching respect for sacred power, the relatedness of all beings, and the care for Earth.

Elk (Cervus canadensis) in Yellowstone National Park. Image credit: Animalia.bio

Current conservation challenges and efforts

Elk face numerous threats, including habitat loss due to climate change, pollution, wildfires, habitat fragmentation, sport hunting, and human encroachment.

Migration pattern tracking and mapping is a practical tool that is proving effective in policymaking and management planning to ensure that natural corridors are at least interrupted as possible.

Preserving the habitat of the elk is vital not just for their survival but for the overall health and resilience of ecosystems and the whole trophic chain. Efforts of Lakota, Cree, Shawnee, Blackfoot, and other Native American Tribes, along with coordinated wildlife conservation initiatives, are crucial for the long-term existence of elk populations.

Explore Earth's Bioregions

%20Waterton%20Lakes%20National%20Park%2C%20Alberta%20AdobeStock_34912613.jpeg?auto=compress%2Cformat&h=600&w=600)