Dr. Jessica Hernandez’s 'Growing Papaya Trees': On reclaiming roots and replanting culture

- Nature Conservation

- Land Conservation

- Indigenous Tenure

- Women

- Social Justice

- Youth Leadership

- Education & Culture

- Climate Heroes

Each week, One Earth is proud to feature a Climate Hero from around the globe who is working to create a world where humanity and nature can thrive together.

Rooted in heritage, raised in resistance

Dr. Jessica Hernandez is many things: an environmental scientist, a writer, an advocate, and a daughter of two nations. She was raised between South Central Los Angeles and southern Mexico, shaped by the wisdom of her Zapotec grandmother and the lived experience of her Salvadoran father, a fisherman and survivor of civil war.

From an early age, Hernandez understood the gap between Western science and Indigenous knowledge. In academic settings, teachings such as oral histories, reciprocal land relationships, and ancestral memory were often dismissed or erased. What others overlooked became her mission. She set out to affirm the legitimacy and strength of Indigenous ways of knowing, especially within the context of climate change and displacement.

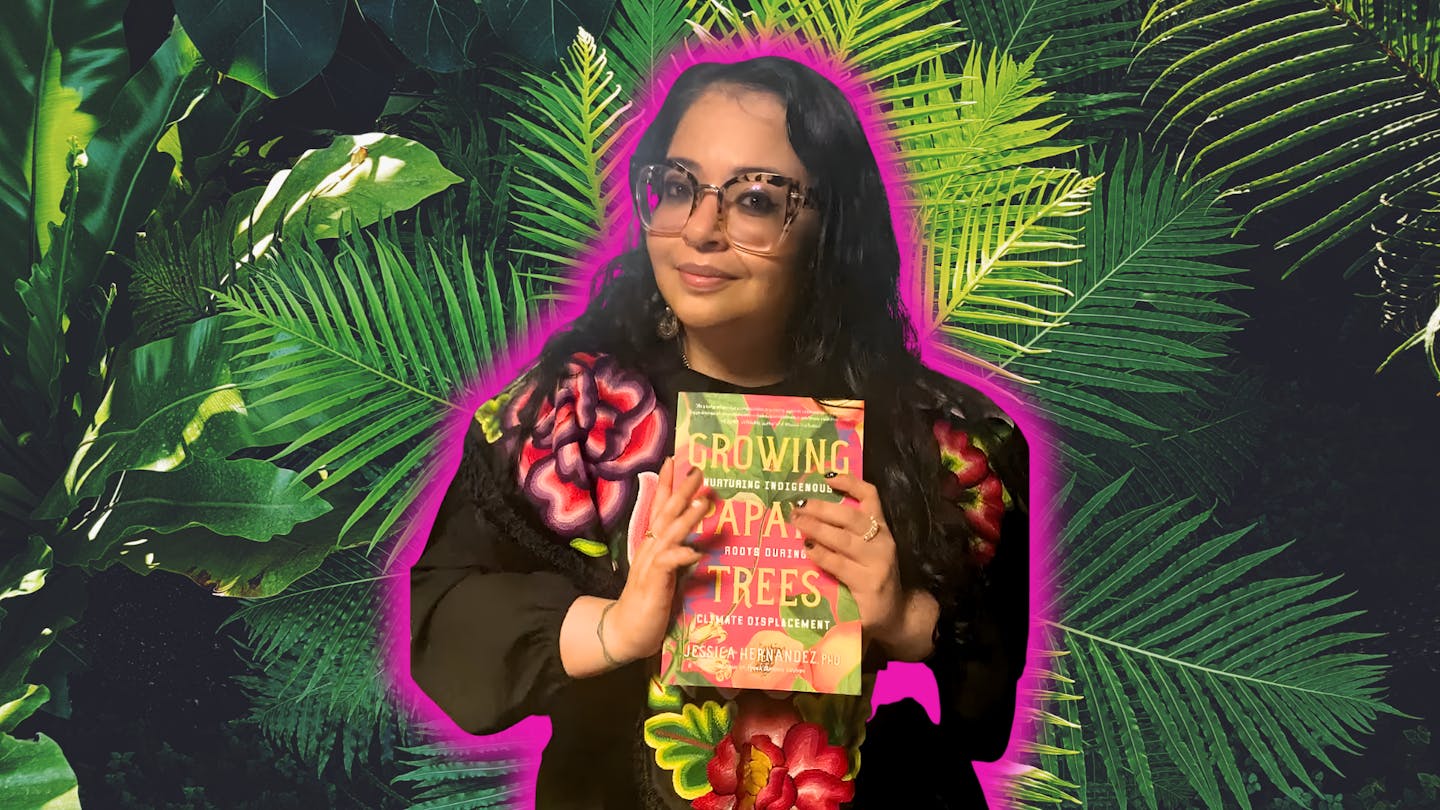

Her first book, Fresh Banana Leaves, offered a direct challenge to conventional conservation frameworks. Her second, Growing Papaya Trees: Nurturing Indigenous Roots During Climate Displacement, goes even deeper. It explores memory, migration, energy justice, and the spiritual experience of being Indigenous while living away from ancestral lands.

Through research, writing, and advocacy, Dr. Hernandez uplifts Indigenous land stewardship and community-led climate justice. Image Credit: @doctora_nature, Instagram.

A love letter to land and memory

The book begins with a heartfelt piece titled “Love Letter to Our Ancestral Lands.” In this poetic opening, Hernandez writes directly to the places that shaped her family’s identity. She frames the land as a living relative, not a resource. Rather than focusing only on trauma, she positions displacement as a site of both rupture and reconnection. This letter becomes an invitation to remember what it means to belong, not just to a place, but to a lineage and a set of responsibilities.

Preparing the Soil: Language loss and cultural survival

In the chapter “Preparing the Soil,” Hernandez reflects on how colonization and forced migration led to the erasure of her family’s Indigenous language. Her father once spoke Nawat, the language of the Pipil peoples of El Salvador, but it was stolen from him through repression and violence. This loss is not just linguistic. It is ancestral, emotional, and ecological.

She uses the papaya as a metaphor throughout the book. It is a fruit that grows easily from discarded seeds, surviving in unexpected places. It becomes a symbol for cultural resilience, showing how displaced people carry ancestral knowledge within them, even when cut off from their homelands.

Preserving Our Lands: The fight for Land Tenure

In “Preserving Our Lands,” Hernandez focuses on the importance of land rights. She explains that reclaiming and protecting ancestral territories is not only about physical space. It is about food sovereignty, cultural survival, and ecological restoration.

The chapter highlights how Indigenous communities have long resisted extraction and development projects. From oil pipelines to mining operations, these threats are not new. What is powerful, however, is how communities are organizing to restore native ecosystems while maintaining traditional stewardship. Hernandez shows how land defense is an act of love, not just resistance.

Harvesting Our Present: Renewable Energy and Indigenous sovereignty

The chapter titled “Harvesting Our Present” explores energy transition through an Indigenous lens. Hernandez raises concerns about how Renewable Energy projects, when designed without community consent, can reproduce colonial patterns. Wind farms, solar installations, and hydroelectric dams have been placed on Indigenous lands without consultation, disrupting ecosystems and spiritual relationships.

She contrasts these examples with community-led efforts that prioritize energy sovereignty. In places where Indigenous communities are generating their own clean power while protecting land and water, true solutions are taking root. Hernandez affirms that energy transition must center self-determination and ecological care, not corporate profit.

Nurturing Seedlings: Youth Leadership and intergenerational resilience

In “Nurturing Seedlings,” Hernandez explores how youth carry ancestral knowledge forward. Even in diaspora, young Indigenous people are reconnecting with cultural practices, traditional foods, and environmental wisdom. She shares her own story of being dismissed in academic spaces, only to later become a mentor for other Indigenous students navigating similar paths.

This chapter highlights the importance of creating space for young people to lead. Hernandez sees youth not as future stewards, but as present-day knowledge holders. Their questions, creativity, and cultural memory are essential to the climate movement and to the survival of Indigenous identities.

Protecting Our Roots: Climate Justice as lived experience

The final chapter, “Protecting Our Roots,” frames climate justice through personal and collective stories. Hernandez ties the global climate crisis to the specific realities of Indigenous peoples, who are disproportionately impacted. From disrupted food systems to forced migration, these communities face layered injustices.

Rather than presenting climate justice as a theory, she grounds it in experience. She writes about grief and resilience, about cultural survival and ecological healing. She shows that for Indigenous peoples, climate change is not abstract. It is already reshaping daily life, and it demands solutions that are both just and rooted in Indigenous leadership.

Dr. Hernandez with her first book, 'Fresh Banana Leaves,' which reclaims conservation through Indigenous science and lived experience. Image Credit: @doctora_nature, Instagram.

Earth Daughters and the work beyond the book

Beyond her writing, Hernandez is the founder of Earth Daughters (Se’e Ñu’un), a collective that supports Indigenous women and youth through mutual aid and climate justice. She also leads Piña Soul, an organization focused on Afro-Indigenous and Indigenous-led initiatives. These efforts reflect her belief that care, healing, and activism must go hand in hand.

Her decision to leave academia was a conscious choice to center community wellness and avoid institutions that perpetuate harm. Through workshops, seed banks, and spiritual practice, Hernandez continues to cultivate spaces where Indigenous knowledge can flourish outside of dominant systems.

Connecting to One Earth: Shared pathways for justice

Dr. Hernandez’s work resonates deeply with the One Earth mission and our science-based Solutions Framework. Her writing aligns with multiple pillars, including Community-Led Renewable Energy, Indigenous Land Tenure, Youth Leadership, and Climate Justice. These are not just policy goals. They are the lived realities of the communities Hernandez uplifts.

At One Earth, we believe that real climate solutions must be place-based, equity-centered, and grounded in Indigenous knowledge. Growing Papaya Trees affirms this. It reminds us that healing the Earth is not only about restoring ecosystems. It is also about restoring relationships, with land, with memory, and with one another.