Circle Economy and the Nature-inspired reinvention of fashion waste

- Regenerative Agriculture

- Circular Fibersheds

- Sustainable Fiber & Pulp

- Green Textiles

- Recycle & Reuse

- Science & Technology

- Climate Heroes

- Greater European Forests

- Western Eurasia Realm

Each week, One Earth is proud to feature a Climate Hero from around the globe who is working to create a world where humanity and nature can thrive together.

In Nature, nothing is wasted

A fallen leaf becomes soil. A decomposing tree becomes shelter. Microbes, fungi, and insects work together to transform what looks like an ending into the beginning of new life. As Asha Singhal, Director of the Nature of Fashion program at the Biomimicry Institute, puts it, “The concept of waste does not exist in Nature.”

The global fashion industry, however, has been built on the opposite idea. Each year, enormous volumes of clothing are discarded, much of it blended, dyed, contaminated, and impossible to recycle. In the Netherlands alone, about 215,000 tons of post-consumer textiles are thrown away annually, with roughly half of it burned in incinerators. Once burned, those fibers, polymers, and chemical building blocks are lost forever, turned into greenhouse gases instead of new materials.

Circle Economy is working to change that trajectory. Through the Nature of Fashion: Design for Transformation initiative led by the Biomimicry Institute, the Amsterdam-based impact organization is leading a groundbreaking pilot in the Netherlands. The pilot project's work shows how even the most difficult textile waste can be transformed, not destroyed, by designing systems that behave more like ecosystems.

Over 100 billion garments are produced every year, and almost all of them are designed for a one-way journey, with less than 1% recycled into new clothes.

Inside the Netherlands pilot: Turning fashion waste into resources

The Netherlands pilot was built to answer one of fashion’s hardest questions: what do we do with the 50 percent of textiles that cannot be reused or recycled and usually end up being burned?

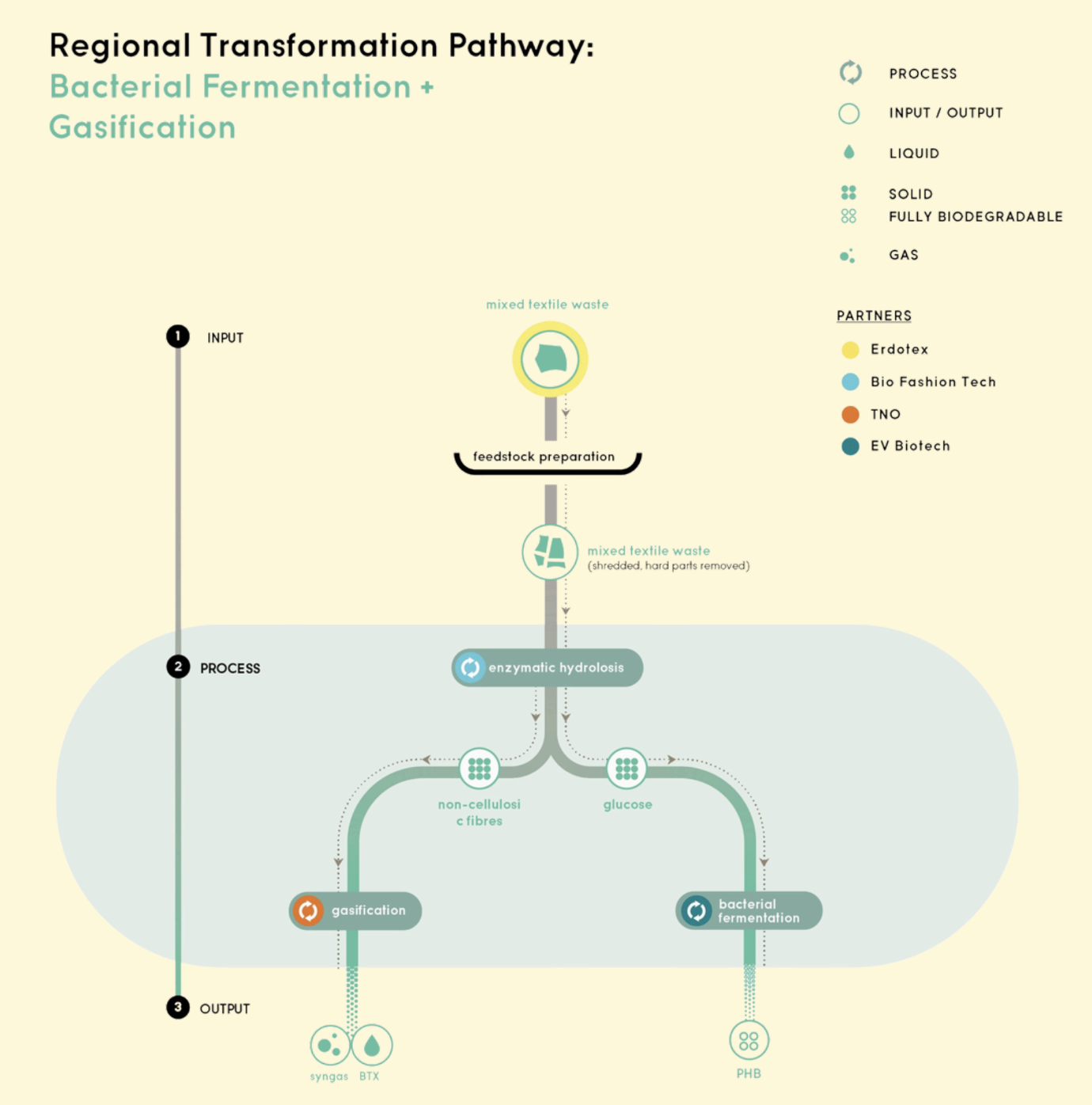

Instead of relying on a single recycling technology, Circle Economy and its partners created a nature inspired decomposition system that treats textile waste the way a forest treats fallen leaves. In ecosystems, breakdown happens through a cascade of organisms, each performing a specific role and passing materials along to the next. The Netherlands system applied that same logic to fashion.

1. Enzymatic hydrolysis: Turning fibers into sugar

Mixed, low value textiles collected through existing municipal systems were first treated with enzymes that broke down cotton, viscose, and other plant based fibers into glucose. This step is crucial because it transforms fabrics that are typically too blended or contaminated to recycle into a clean biological feedstock that can be used again.

2. Fermentation: Growing bioplastics from old clothes

That glucose then became food for microbes, which converted it into PHA, a fully biodegradable bioplastic. Instead of relying on fossil fuels or agricultural crops, this process uses the carbon locked inside discarded clothing to grow new materials that can be used in packaging, agriculture, and other applications.

3. Gasification: Transforming what remains

After the plant based fibers were removed, what remained, including polyester, nylon, and other synthetic materials, was processed through thermochemical gasification. This transformed the so-called unrecyclable fraction of textiles into syngas, methane, and methanol, chemical building blocks that can replace fossil based inputs in fuels and industrial products.

Nothing was burned or dumped. Every fraction of the discarded garments became something useful again.

The pilot delivered results that surprised even the scientists. Glucose made from old clothes performed as well as, and sometimes better than, virgin glucose in fermentation. Gasification also became more efficient when textiles were enzymatically treated first.

A new life for old clothes: Circle Economy and its partners developed an integrated system that turns textile waste into sugar, bioplastics, and clean chemical feedstocks, showing how even the hardest-to-recycle garments can be transformed instead of burned.

Designed for mixed and changing materials

The system was developed to be modular and adaptable, capable of handling textile waste streams that change in composition over time. Because clothing materials vary from day to day and year to year, the pilot focused on working with mixed and inconsistent inputs rather than relying on tightly sorted, uniform feedstocks.

This flexibility reduces the need for intensive sorting and makes the system more resilient to changes in textile materials over time. As additional bio-based technologies develop, the approach can expand to include new pathways for materials like polyester and nylon, building on this adaptable foundation as fashion continues to evolve.

A new chapter for the Nature of Fashion

This pilot is the first case study to emerge from the Biomimicry Institute’s Nature of Fashion: Design for Transformation initiative, a global effort to rethink fashion and textiles through the lens of nature’s operating systems. The initiative recognizes that the current take, make, and waste model has exceeded planetary limits, and that true circularity will only be achieved by learning from how living systems safely break down and rebuild materials.

Rather than focusing on better versions of the same industrial logic, Nature of Fashion explores how decomposition, fermentation, and regeneration can become core functions of the fashion system itself. Through regional pilots in places like the Netherlands, Germany, and Ghana, the initiative is testing how biological and thermochemical processes can be combined to turn complex textile waste into materials that are safe for both people and ecosystems.

Circle Economy’s work in the Netherlands offers one of the clearest demonstrations yet that this vision is not theoretical. It is already working.

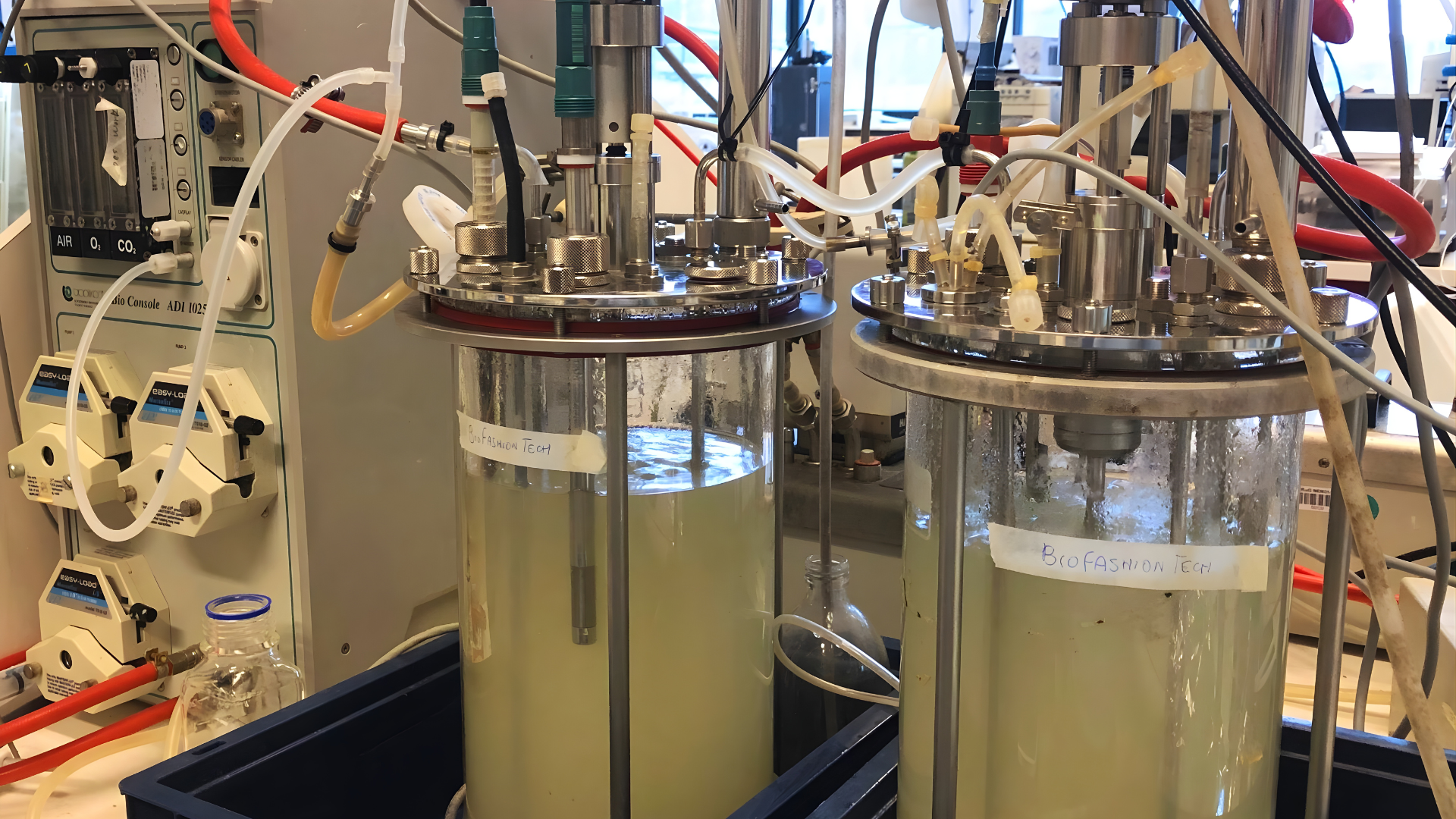

As part of the Netherlands pilot, bacterial fermentation transforms sugars recovered from old textiles into biodegradable PHA bioplastics. Photo by Fabiola Polli from BioFashionTech.

A bioregional future for fashion

While the Netherlands pilot is a working prototype, its implications will hopefully reach far beyond one country. As Asha Singhal shared with One Earth, “Textile waste is everywhere, but it is unevenly distributed.” The Global North produces and consumes most of the world’s clothing, while much of the environmental and social burden is pushed onto communities in the Global South through exports of secondhand and unusable garments.

Looking ahead, the vision is for regional bio hubs that can map local textile waste streams, local industries, and local innovators to build systems that transform fashion waste into materials, jobs, and economic value close to where it is generated. In the Global North, that means stopping the export of harm and taking responsibility for what we consume. In the Global South, it means creating local systems that turn legacy waste into renewal rather than environmental collapse. This does not yet exist, but it is the future this work is pointing toward.

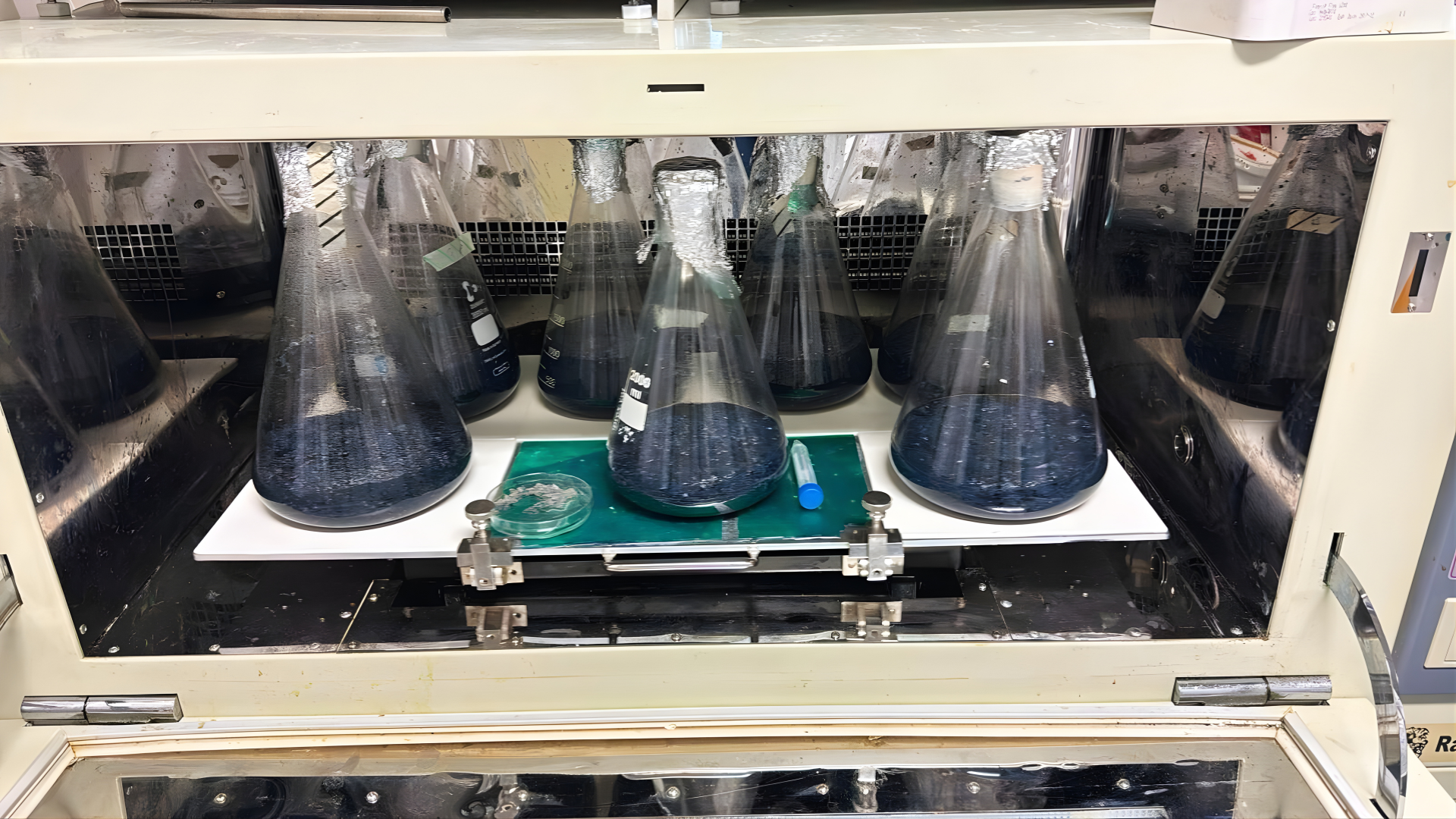

Through this integrated system, enzymatic hydrolysis breaks down plant-based fibers in textiles into recoverable glucose. Photo by Fabiola Polli from BioFashionTech.

Connecting to One Earth’s Solutions Framework

This work aligns directly with One Earth’s Solutions Framework through the Circular Fibersheds subpillar, which focuses on designing fiber and textile systems that regenerate ecosystems, eliminate waste, and keep materials flowing safely through nature and industry. Solutions such as Sustainable Fiber & Pulp, Green Textiles, and Recycle & Reuse all seek to replace today’s extractive fashion economy with one that is circular, place-based, and life-supporting.

Circle Economy’s Netherlands pilot brings that future into focus. By turning discarded clothing into sugar, bioplastics, and chemical building blocks through a nature-inspired system, they are proving that fashion does not have to end in smoke and ash. It can become part of a continuous cycle of transformation, where even the most difficult waste is returned to life.

Read the full case study

.jpeg?auto=compress%2Cformat&h=600&w=600)