Tundra wolf: Guardian predator of the Arctic ecosystem

- Nature Conservation

- Land Conservation

- Iconic Species

- Wildlife

- Sea of Okhotsk & Bering Tundra/Taiga

- Subarctic Eurasia Realm

One Earth’s “Species of the Week” series highlights iconic species that represent the unique biogeography of each of the 185 bioregions of the Earth.

Picture a stark, sprawling Arctic river valley in northern Siberia: snow-crusted, wind-scoured, the light pale and crisp. Through the winter twilight, a ghostly pack of grey wolves glides along the edges of the tundra. Among them moves the impressive Tundra wolf (Canis lupus albus), also known as the Turukhan wolf, a predator built for extremes.

This subspecies is crucial: as one of the apex predators of the Eurasian tundra and forest-tundra zones, it plays a vital role in shaping ecosystem dynamics in one of the planet’s most remote and fragile biomes.

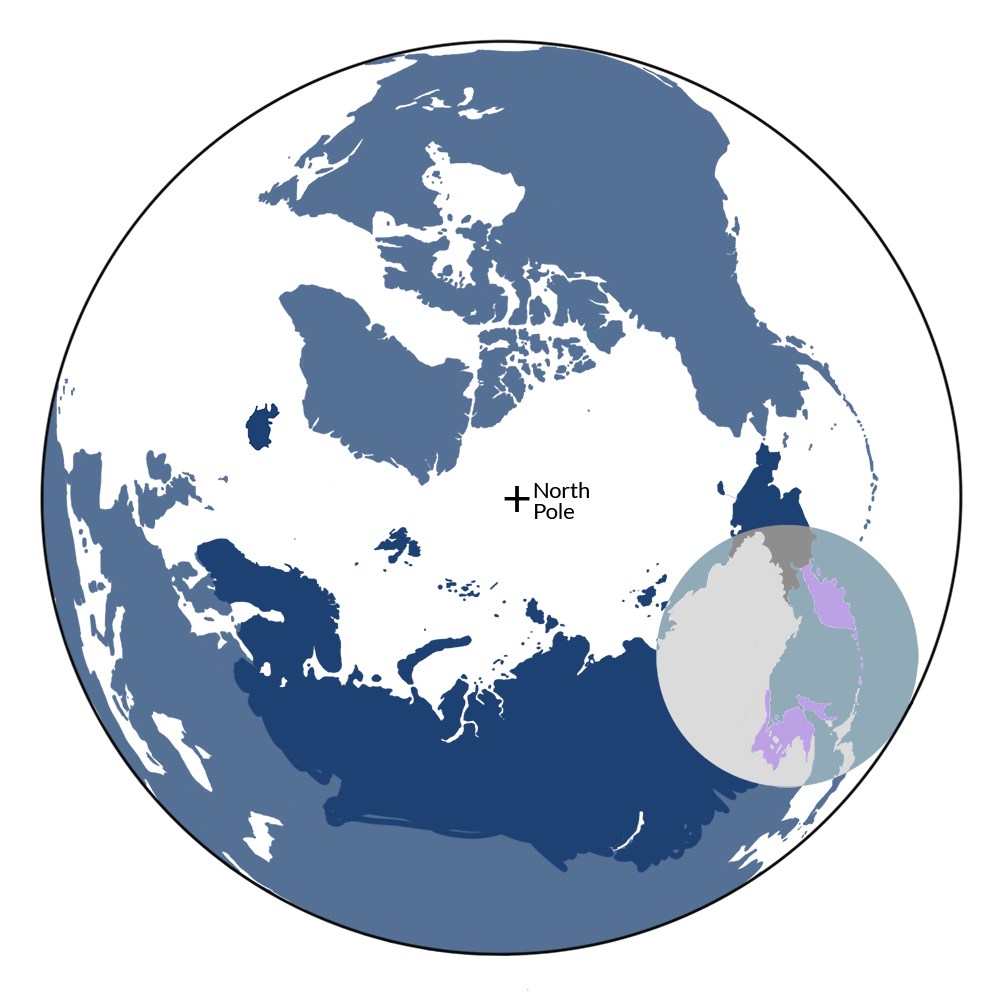

The Tundra wolf (Canis lupus albus) is the iconic species of the Sea of Okhotsk Coastal Taiga, Meadows & Tundra bioregion (PA6) located in the Sea of Okhotsk & Bearing Tundra-Taiga subrealm of Subarctic Eurasia.

Habitat and environment

The Tundra wolf inhabits the vast stretches of tundra and forest-tundra across northern Eurasia—from northern Finland to Siberia and the Kamchatka Peninsula. In these regions, the seasons swing dramatically: short, intense summers and long, brutal winters, with deep snow and temperatures plunging far below freezing.

Adaptations to this harsh habitat are evident. The Tundra wolf rests and travels in river valleys, shrubby thickets, and forest clearings—areas where prey congregate and movement is possible despite deep snow. Their long legs are built for moving through snow, their fur is dense and insulating, and their hunting behavior follows migratory ungulate herds across the tundra.

Yet this environment is under threat. Climate change is rapidly transforming tundra ecosystems by melting permafrost, shifting vegetation zones, and altering prey distributions. For a predator so closely tied to tundra prey such as reindeer, these shifts pose risks that ripple across the entire ecological network.

Tundra wolf in the wild. Image Credit © L.Mormile, Depositphotos.

Physical traits and behavior

The Tundra wolf is a large and striking carnivore. Adult males measure 118–137 cm in body length, while females range from 112–136 cm. Average weights are around 40 kg for males and 36.6 kg for females, with exceptional individuals historically reaching up to 52 kg.

Its coat is long, fluffy, and extremely dense, an essential insulation in sub-Arctic conditions. The upper hairs can reach 150–160 mm in length, with thick, soft underfur beneath. Coloration tends to be very light grey, often with subtle reddish or ochre tinges on the upper parts, and a lighter “lead-gray” undercoat.

Behaviorally, these wolves live in social packs and use cooperative hunting to take down large prey—particularly wild or domestic reindeer in winter. In one study of 74 wolves in the Nenets Autonomous Okrug, 93.1% of winter stomach contents consisted of reindeer remains. During summer, their diet diversifies to include newborn reindeer calves, birds, small rodents, and hares.

Reproduction follows the typical wolf pattern: breeding occurs in late winter or early spring, with a gestation of about 63 days and pups born in a den or sheltered site. While specific data for the Tundra wolf is limited, this pattern aligns with that of the broader gray wolf (Canis lupus), making it a reasonable assumption here.

Interestingly, field observations suggest that these wolves may travel vast distances following prey migrations. Some territories span hundreds of kilometers across the Arctic.

Ecological significance

The Tundra wolf plays a pivotal role in the ecosystems along the boreal-Arctic edge. By regulating populations of large herbivores like reindeer and caribou, they influence vegetation dynamics: fewer overgrazing animals mean healthier tundra plant communities, which in turn support other species (e.g., birds, rodents) and enhance carbon sequestration.

Imagine a winter scene: a pack of Tundra wolves shadows a reindeer herd across the snow, selectively picking off the weak or the calves. This predation helps maintain a healthier prey population and prevents over-browsing of lichen and moss beds—key carbon sinks in the tundra.

If these wolves were to decline significantly, ecosystems could destabilize. Unchecked herbivore populations might degrade critical tundra vegetation, altering microclimates, accelerating thaw rates, and shifting the timing of spring melt. The consequences would ripple far beyond a single predator.

Cultural and mythological significance

In the remote regions of northern Eurasia—among the Sámi, Nenets, and other Indigenous peoples—the wolf holds deep cultural significance. While the Tundra wolf specifically may not appear frequently in recorded legends, the wolf as a symbol resonates: representing strength, endurance, and the wild margins of civilization.

For the Nenets, whose reindeer-herding lives intersect with wolf territories, the wolf is both revered and feared: a creature of the tundra that tests the boundaries of human-animal coexistence. Stories speak of wolves as guardians of the border between the human world and the wild, of wolves traveling with the wind and vanishing into the endless white.

In Nenets lore, the wolf-spirit Pana embodies the resilience of tundra life: the pack is seen not merely as a predator, but as a reflection of the migratory rhythms shared by reindeer, herders, and humans.

%20running%20in%20the%20winter%20snow.%20Image%20credit%20Jim%20Cumming%20Depositphotos.jpeg)

Tundra wolf running in the winter snow. Image Credit: © Jim Cumming, Depositphotos.

Conservation status and challenges

The Tundra wolf is currently listed as Near Threatened in Finland. Its overall population is not well quantified due to its remote range and the vast territories it occupies.

Major threats include:

- Habitat change: Tundra warming, shrub encroachment, and permafrost thaw are altering prey distributions.

- Prey decline: Changes in reindeer and caribou populations affect food availability.

- Human/wildlife conflict: Predation on domestic reindeer leads to lethal control. (Between 1944–54, an estimated 75,000 reindeer were lost to tundra wolves in some Russian regions.)

- Isolation and genetic concerns: Remote populations may face inbreeding and reduced resilience.

- Climate change: As the Arctic warms faster than any other region, the Tundra wolf’s specialized adaptations may become mismatched to shifting prey and vegetation dynamics.

Conservation efforts

Research remains limited, particularly in terms of genetics, but awareness is growing. Community engagement, including strategies for herder-wolf coexistence, is essential. Equally important is protecting large, connected landscapes so wolves can follow migratory prey.

In the vast emptiness of the Arctic tundra, the Tundra wolf moves like a living thread of wilderness—an icon of survival in one of Earth’s harshest realms. Protecting this species means preserving the integrity of the tundra itself: its unique ecology, slow-growing shrubs, rich mosses, and the ancient rhythms of snow and ice.

Support Nature Conservation-

-

Heptner, V.G. & Naumov, N.P. (1998) Mammals of the Soviet Union, Vol. II, Part 1a: Sirenia and Carnivora (Sea cows; Wolves and Bears)

-