American badger: The powerful digger of North America's grasslands

- Nature Conservation

- Land Conservation

- Iconic Species

- Wildlife

- Mammals

- American West

- Northern America Realm

One Earth’s “Species of the Week” series highlights iconic species that represent the unique biogeography of each of the 185 bioregions of the Earth.

Low to the ground, broad-shouldered, and armed with formidable claws, the American badger (Taxidea taxus) is one of North America’s most effective underground hunters. Built for life below the surface, this solitary carnivore has shaped grassland ecosystems for millions of years, quietly influencing everything from rodent populations to the fate of other burrow-dwelling wildlife.

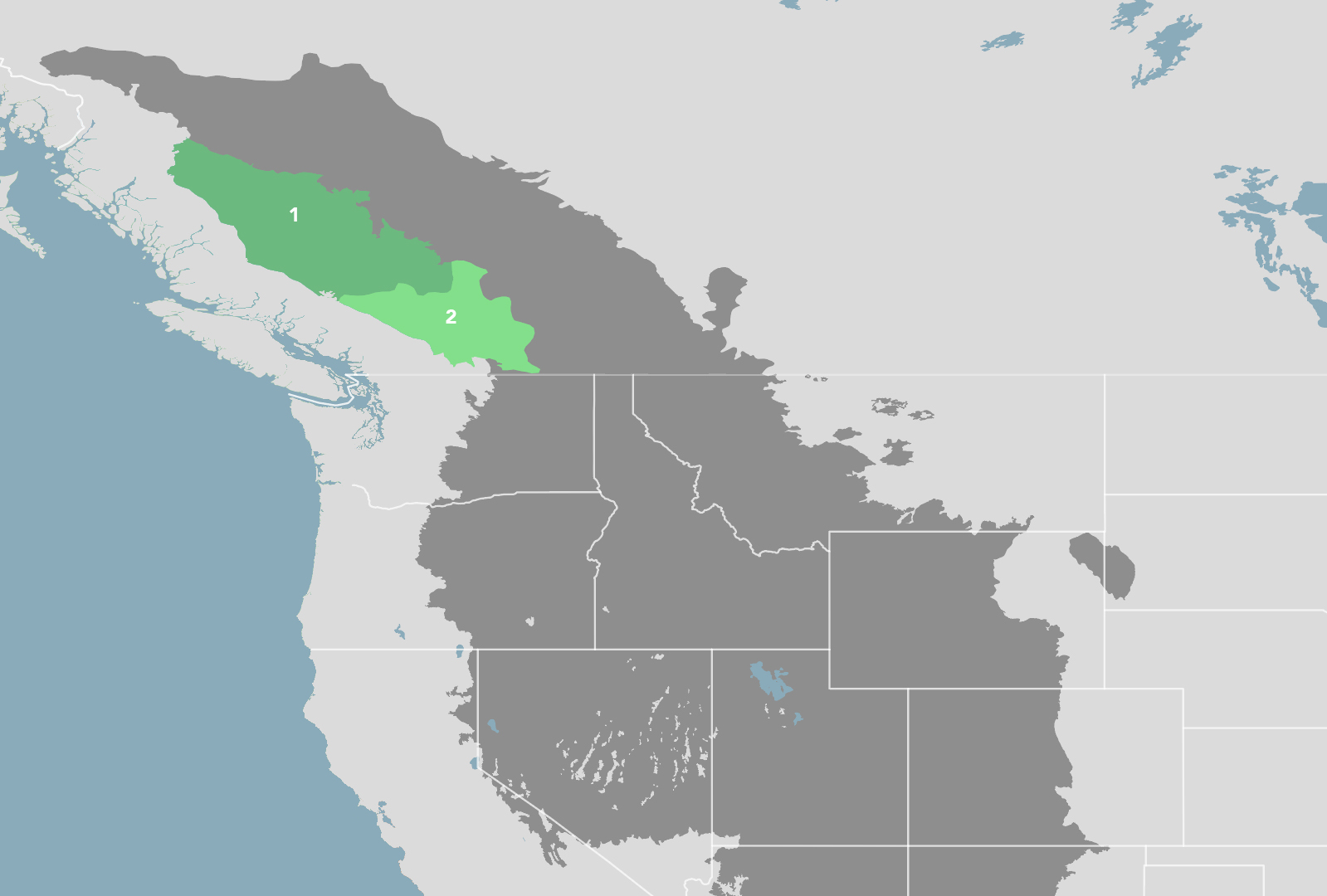

In the One Earth Bioregions Framework, the American badger is the iconic species of the Northwest Intermountain Conifer Forests bioregion (NA14), located in the American West subrealm of Northern America.

Life across the open country

American badgers are found across the western, central, and northeastern United States, northern Mexico, and south-central Canada, extending into parts of southwestern British Columbia. Their ideal habitat includes open grasslands, prairies, parklands, agricultural fields, and other treeless or lightly wooded areas with permeable soils. Sandy loam soils are especially important, allowing badgers to dig efficiently while pursuing prey.

They can also occupy forest glades, meadows, shrub-steppe, marsh edges, desert scrub, and mountain meadows, sometimes at elevations over 3,600 meters (12,000 ft). Across this wide range, access to rodent prey and suitable digging conditions remains the defining feature of badger habitat.

A body built to dig

The American badger has a stocky, low-slung body supported by short, powerful legs. Its most striking tools are its massive foreclaws, which can reach up to 5 centimeters (2 in) long. These claws, combined with a strong humerus and specialized forelimb bones, give the badger exceptional digging power.

Adults typically measure 60 to 75 centimeters (23.5—29.5 in) in length. Females generally weigh about 6.3 to 7.2 kilograms (14—16 lb), while males can reach up to 8.6 kilograms (19 lb), with some northern individuals weighing significantly more in fall when food is abundant.

The coat is coarse and grizzled, blending brown, black, and white tones that provide camouflage in grassland environments. A triangular face features bold black and white markings, including a white stripe running from the nose to the back of the head, and in some subspecies, extending all the way to the tail.

An American badger in the winter snow. Image Credit: © Jim Cumming, Dreamstime.

Underground predators of the plains

American badgers are fossorial carnivores, meaning they specialize in hunting prey underground. Their diet centers on small mammals such as pocket gophers, ground squirrels, prairie dogs, marmots, moles, voles, deer mice, kangaroo rats, and woodrats. They often dig directly into burrows, sometimes sealing tunnel exits to prevent escape.

They are also notable predators of snakes, including rattlesnakes, and are considered a key rattlesnake predator in parts of South Dakota. Beyond mammals and reptiles, they consume ground-nesting birds, lizards, amphibians, insects, carrion, fish, and occasionally plant foods such as corn, beans, mushrooms, and sunflower seeds.

Engineers of grassland ecosystems

By controlling rodent populations, American badgers help regulate species that can otherwise heavily alter vegetation and soils. Their digging behavior aerates soil, redistributes nutrients, and creates burrows that are later used by many other species.

Abandoned badger dens provide shelter for foxes, skunks, burrowing owls, tiger salamanders, and even amphibians like the California red-legged frog. In this way, a single badger can indirectly support a wide web of grassland life.

American badger spotted in Oregon, east of the Cascade Mountain Range. Image Credit: Nick Myatt, Oregon Department of Fish and Wildlife, Wiki Commons.

Ecology and behavior

American badgers are generally nocturnal, though they are often active during the day in remote areas or during spring, when females forage while caring for young. They do not hibernate, but in winter they may enter cycles of torpor lasting about 29 hours, emerging when temperatures rise above freezing.

Badgers are skilled scratch diggers, using their forelimbs to break soil and push debris behind them. They frequently dig new burrows, sometimes creating one to three in a single day during periods of active foraging. These dens may be used briefly and then abandoned, only to be reused later if prey remains abundant.

One of the most remarkable behaviors documented in American badgers is their cooperative hunting with coyotes. By working together, the badger blocks underground escape routes while the coyote chases prey above ground, increasing hunting success for both animals.

Reproduction and life cycle

American badgers are solitary except during the breeding season. Mating occurs in late summer and early fall, but females experience delayed implantation, with pregnancies resuming months later. Young are born from late March to early April in litters of one to five, with an average of three.

Newborns are blind and helpless. Their eyes open at four to six weeks, and they begin emerging from the den around five to six weeks of age. Families typically break up by early to mid-summer, when juveniles disperse to establish their territories.

Most females breed for the first time after one year of age, while males usually do not breed until their second year. In the wild, American badgers typically live 9 to 10 years.

Threats to badgers and human impacts

Adult American badgers have few natural enemies, but juveniles may fall prey to golden eagles, coyotes, and bobcats. Adults are occasionally killed by bears, gray wolves, and cougars, which appear to be one of their most significant predators in some regions.

Human activities pose additional threats. Habitat fragmentation and overdevelopment have reduced available grasslands, forcing badgers into closer contact with people. Badgers have also been trapped historically for their fur, which has been used in shaving and painting brushes.

American badger in the summer. Image Credit: © Geoffrey Kuchera, Dreamstime.

Conservation status and protection efforts

The conservation status of the American badger overall is Least Concern but varies by region. In Canada, several subspecies are listed under the Species at Risk Act, with some populations classified as endangered and others as being of special concern. In California, the species is designated as a species of special concern due to habitat loss and fragmentation.

Conservation efforts increasingly focus on protecting large, connected grassland habitats, identifying important breeding and denning areas, and reducing conflicts between badgers and human development.

A quiet force beneath the fields

Rarely seen but constantly at work, the American badger is a reminder that some of the most influential animals shape ecosystems from below the surface. Through relentless digging and solitary hunting, this powerful mammal helps keep North America’s open landscapes alive, balanced, and full of hidden connections.

Support Nature Conservation